Read by Maja Zamiejska

This review contains spoilers

The gothic event of the season, Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein bears the unmistakable imprint of a filmmaker with a spectacular imagination. A film of lavish beauty, with the sets and costumes so polished that they look deliberately artificial, it reveals as much about its creator as the Creature reveals about Baron Frankenstein.

Throughout his career, del Toro has been forcing the viewer to feel sympathy for many of his monsters. In Cronos (1992), a kind old man becomes a vampire but refuses to feed on his granddaughter. In The Devil’s Backbone (2001), a scary ghost is revealed to be a victim rather than a villain. The title protagonist of Hellboy (2004) and Hellboy II: The Golden Army (2008) is presented as a demonic messiah with a gruff exterior and a heart of gold. Both Hellboy films involve various beings that could be featured in the Universal Studio Monsters movie franchise in the 1930s-1950s, but turn out to be heroic, graceful, intelligent and likeable. Finally, The Shape of Water (2017) presents a love story between a humanoid amphibian being, resembling Universal Studio’s Creature from Black Lagoon, and a woman who discovers she has more in common with her lover than just inability to speak.

Perhaps it is no wonder then that in his newest film, which he directed, co-produced, and wrote, del Toro turns Frankenstein’s Creature into a being of tragic beauty rather than abject terror. Here the monster made of several corpses sewn together resembles a statuesque elf, Prince Nuada from Hellboy II, a far cry from Boris Karloff’s iconic portrayal of Frankentein’s monster in Universal’s 1931 film. One could argue that this appearance is more faithful to the original novel, but I have my doubts.

After all, Mary Shelley makes Frankenstein describe the Creature he just made in the following manner:

His limbs were in proportion, and I had selected his features as beautiful. Beautiful!—Great God! His yellow skin scarcely covered the work of muscles and arteries beneath; his hair was of a lustrous black, and flowing; his teeth of a pearly whiteness; but these luxuriances only formed a more horrid contrast with his watery eyes, that seemed almost of the same colour as the dun-white sockets in which they were set, his shrivelled complexion and straight black lips. (55-56)

From the above excerpt, as well as the reaction of everyone who sees the Creature, I conclude that he is supposed to embody horror, that is, to use Noël Carroll’s terminology, evoke fear and disgust (28). It is questionable whether Jacob Elordi’s Creature, even in the makeup that took the grueling 10 hours to apply (Hart), evokes such feelings.

I did not mention Prince Nuada accidentally. The actor playing the elf ruler, Luke Goss, who also starred as the villain in del Toro’s Blade II (2002), played the Creature in the underrated Hallmark miniseries Frankenstein (2004). And while the TV budget certainly limited that production, the overall look of the Creature corresponds more to Shelley’s description, combining beauty with disgust, as the yellowish, wrinkled skin on his face actually seems spread on too large a canvas. In Frankenstein (2025), the grayish makeup evokes an anatomy model, a choice del Toro himself explained in his interview with Terry Gross:

I wanted it to feel like an anatomical chart, like something newly minted. . . . The head is patterned after phrenology manuals from the 1800s. So they have very elegant, almost aerodynamic lines. I wanted this alabaster or marble, statue feel, so it feels like a newly minted human being. And we also tried to make it the way I remember the Jesus images, life size, in the churches of my childhood.

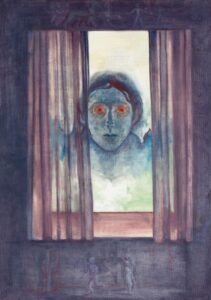

As a result, the audience is no longer faced with the Other, the undead, the monster but a superhuman or even a god. Bride of Frankenstein (1935) already uses visual imagery comparing the Creature to Christ on the cross, but Karloff still looks definitely nonhuman there, especially with metal bolts in his neck. While both 2004 and 2025 adaptations do not use Shelley’s “watery, clouded eyes of the monster” (225), the newest film shows the Creature as much closer to physical perfection.

I devoted so much space to this new look because I feel it corresponds to the changes done to the plot and the character as such. Shelley’s and most filmmakers’ Creature is a being of moral ambiguity. He is capable of both tenderness and violence. He kills innocent people driven by the need for revenge on his creator. Del Toro, however, purifies him. The Creature’s violence becomes episodic and accidental rather than integral and while he kills six men in the opening scene, he does not commit some of the crucial murders from the book. Thus, this Creature appears to be a misunderstood Romantic or even Byronic hero (the film ends with the quote from Lord Byron), driven to violence mostly due to mistreatment by a sadistic Frankenstein or hurt from other people who shoot first, ask questions later.

When it comes to the production design, it evokes nineteenth-century Europe with details bordering on reverence. The effect deepens in scenes that directly reference famous paintings (see the video compilation from A Shot magazine linked below). All this beauty, while impressive, may result in too few distortions that one tends to expect from the gothic genre. Even del Toro’s Crimson Peak (2015), as visually stunning as it is, includes signs of destruction and decay in the title estate. Here, the locations look like an airbrushed dreamscape. At times one can forget this is a story about dead flesh coming to life. Constructing the full body out of corpses, while involving a large amount of blood, mirrors assembling a complicated machine or detailed sculpture.

The tendency to favor the aesthetic is not new in del Toro’s oeuvre, but in Frankenstein it reaches an extreme that challenges the film’s thematic aspirations. While the plot follows the main events of the original, it decreases the number of the Creature’s crimes and adds a romantic subplot between him and Elizabeth, thus turning a classic gothic/science fiction horror into a gothic melodrama.

Named Elizabeth Harlander in this adaptation, Mia Goth’s character is no longer Victor Frankenstein’s fiancée but is engaged to his younger brother, William. I suspect that this change allowed her character to be more suspicious of her future brother-in-law’s actions. Oscar Isaac’s intense performance as Victor Frankenstein stresses the scientist’s cruelty and manipulation (his scheming nature evokes Peter Cushing’s portrayal in The Curse or Frankenstein [1957]) while Goth plays Elizabeth as a skeptical intellectual who is still capable of kindness. Elizabeth joins other female characters in del Toro’s works who feel connection to the monster, whether romantic, as in The Shape of Water and Hellboy or spiritual, as in Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), but her relationship with the Creature is perhaps the most tragic.

All things considered, del Toro’s approach, especially towards such an iconic plot, is divisive. While I enjoyed the film, I also discovered I might be too attached to my understanding of Frankenstein as horror rather than melodrama to like everything about this adaptation. The script clearly uses the common interpretation of Frankenstein being the Creature’s symbolic father, but stresses the emotional impact of him abusing and abandoning his son. And what is more, this version of the Creature has much in common with the title wooden puppet in Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio (2022). Instead of ending his animated film with the puppet becoming a “real boy,” the director shows Pinocchio’s father being perfectly happy that his beloved child is alive and unchanged. Pinocchio, the immortal being, is thus fully accepted in his “monstrous,” wooden form by his creator. In Frankenstein, Victor apologizes to his similarly immortal child, calling him “my son,” and is granted forgiveness. Their final moments together are peaceful. After Victor dies, the Creature remarks, “Perhaps now, we can both be human.” This suggests that only when the cruel father finally accepts his son on his deathbed, he symbolically earns his humanity. Personally, I find their reconciliation rushed and unbelievable. What fits a fairy tale may not fit a gothic horror as well. In the original novel, on his deathbed, Frankenstein still calls the Creature “my enemy and persecutor, . . . my adversary” (268) and wants him dead. He dies without meeting his enemy again. The cruel father learns a different lesson at this point, that of not playing God.

Shelley concludes her novel with the monster declaring he will set himself on fire, thus breaking the cycle of abuse against nature. Del Toro allows only sunrays to caress the Creature’s face, thus embracing his connection to nature. The beautiful godlike being chooses to live and enjoy the life he was given. The film ends on a hopeful note that he may thrive, just as the director wants his monsters to.

Works Cited

Carroll, Noël. The Philosophy of Horror or Paradoxes of the Heart. Routledge, 1990.

Del Toro, Guillermo. “Filmmaker Guillermo del Toro says ‘I’d rather die’ than use generative AI.” Interview by Terry Gross, NPR, 23 Oct. 2025, https://www.npr.org/2025/10/23/nx-s1-5577963/guillermo-del-toro-frankenstein.

Frankenstein. Directed by Guillermo del Toro, Netflix, 2025.

Hart, Hugh. “42 Prosthetics, 10-Hour Nights: How Prosthetics Master Mike Hill Turned Jacob Elordi Into the Creature for Guillermo Del Toro’s ‘Frankenstein.’” The Credits, 7 Nov. 2025, https://www.motionpictures.org/2025/11/a-newly-minted-man-how-mike-hill-brought-frankenstein-to-life-for-guillermo-del-toro/.

Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. 1818. Pocket Books, 2004.

A Shot [@ashotmagazine]. Video compilation of art references in Frankenstein. Instagram, 10 Nov. 2025, https://www.instagram.com/reel/DQ3YJrcjDNJ/.

Films mentioned

Frankenstein (1931)

Bride of Frankenstein (1935)

Creature from The Black Lagoon (1954)

The Curse of Frankenstein (1957)

Cronos (1992)

The Devil’s Backbone (2001)

Blade II (2002)

Frankenstein (2004)

Hellboy (2004)

Pan’s Labyrinth (2006)

Hellboy II: The Golden Army (2008)

Crimson Peak (2015)

The Shape of Water (2017)

Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio (2022)