This issue centers on the word loyalty—a concept that unfolds into questions of choice, demand, duty, and betrayal. Gothic loyalty may be tender or terrifying, inherited or invented, sacred or broken. In everyday life we concede that loyalty is the bare minimum: we expect our friends not to betray us. Yet the universe grows bleak when loyalty becomes the only currency left.

In the gothic imagination, loyalty is never simple. The friend who guards our secrets may one day betray us; the authority who commands our devotion may wield it as leverage. And countries—haunted houses of allegiance—offer safety only in exchange for dignity, demanding that we remain loyal even as we count the many ways we have already been betrayed.

The gothic imagination insists on a distinction between loyalty and fealty, even as the two entwine. Loyalty is voluntary; fealty—obligatory. Loyalty can be freely given; fealty is demanded, ritualized, and binding. Loyalty is felt; fealty is sworn; yet children are expected to be unequivocally loyal to their elders; in every hierarchical arrangement fealty is presumed, presupposed, and enforced. We recognize this pattern in Sarah Flamminio’s “The Province of Pain.”

Loyalty is modern, circulating freely in friendships, families, and countries. Fealty belongs to the gothic lexicon of oaths, vassals, queens, princes, and servants, creating a haunted circle where no loose ends are allowed. If you insist on becoming one, you may try it out for a while, but eventually someone is bound to die—as in Adrian Kafarski’s “The Thorn Prince.”

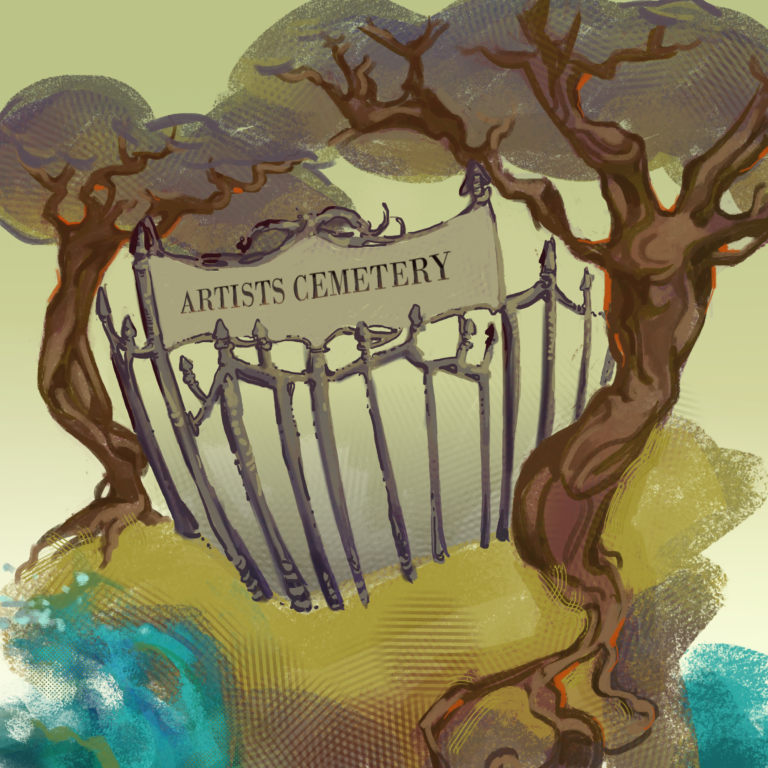

Paulina Jakimowicz’s “The Artists Cemetery” testifies to a different kind of loyal submission. By turns coolly and derisively, the cemetery keeper comments on hapless artists who come to bury their failed works in a surreal location by the sea. His ruminations disclose much about the fate of the defeated, but almost nothing about himself, which makes his voice all the more uncanny. One suspects these artists failed not for lack of talent, but because the bond of loyalty to parents, teachers, or supervisors outweighed trust in their own creative path. Success would have meant betrayal—an unforgivable crime against those authority figures who once pronounced their work worthless. And how can you live with such betrayal? Safer to admit defeat, to provide proof that your efforts were indeed nothing. To carry such a bond in your head is to live under a spell of gaslighting. And to break free from it, you must become more than a little disloyal.

At other times loyalty can be self‑inflicted, ritualized, and organically true, as in “Winter Again” by Oliwia Sewastynowicz, where the grieving narrator positions themselves beyond our reach. This voice is not Poe’s typical unreliable narrator, but rather fragmented and traumatized—lucid in its grief, yet fractured by loss. The narrator does not expect us to follow suit; their loyalty to mourning is solitary, not coercive. A grieving person is expected to grieve “reasonably” for a certain period of time—a week, a month, perhaps a year at most. Never are you to grieve for another winter; that excess is forbidden. And yet “Winter Again” insists on this excess, until loyalty to grief itself becomes both a ritual and a resistance.

Aris Kowalski’s “A Letter from an Old Friend” turns on the fragile axis of friendship and betrayal. Gothic friendships rarely rest on ordinary trust; they hinge on secrecy, shared trauma, or forbidden knowledge. In such narratives, the secret need not be revealed—indeed, a zealous writer who exposes or encrusts it in too many details shifts the story from gothic to political fiction. Here lies the double meaning of secrecy: loyalty demanded by authority figures is coercive, but loyalty in friendship often means preserving your friend’s silence, or accepting that they are entitled to keep a secret at all.

“The King’s Greatest Soldier” by Kamil Mania paints a dystopian panorama that echoes daily headlines. Here, loyalty to country becomes a gothic contract: protection offered, dignity surrendered. Once you become a devotee of toxic nationalism, sooner or later you will be expected to disown a family member, denounce them, abandon them, throw them under the bus. Distancing yourself from your own kin becomes the cruelest currency of allegiance. To picture the homeland as a haunted house, demanding submission even as it decays, is a gothic trope—here set not in a fortress but in a simple prairie house, isolated by wind and distance, where political loyalty itself becomes the machinery of betrayal.

The gothic imagery of contracts, oaths, blood, and shadows frames allegiance as both sacred and sinister. Katarzyna “Catharsis” Mikołajczyk’s review of FAITH: The Unholy Trinity and Alicja Chmiołek in her discussion of “Beautiful Creature” in Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein” both explore this precarious equilibrium between the sacred, the profane, and the forbidden. Mary Shelley’s nineteenth‑century novel gave us a doctor who gaslights and manipulates but never murders; del Toro’s film makes the responsibility explicit, laying it on the parental figure. The gothic lesson is clear: authority that demands fealty betrays time and again the unfortunate humanoid creature. All that’s left is a sad thought: “here we go: the same ritual of abuse, the same failure of guardianship.”

In the Art/Work section we feature renowned artist artist Aleksandra Waliszewska. Her Battle of Grunwald, previously shown at her retrospective in the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, deliberately echoes Jan Matejko’s 1878 canvas, painted to raise national morale after the failed January Uprising of 1863. Matejko’s original Battle of Grunwald depicted the 1410 victory of Polish and Lithuanian forces over the Teutonic Order. Yet history reminds us that it took more than a century to finally remove the Order from the Baltic Sea area: precisely in 1525 its territory was secularized into the Duchy of Prussia under Polish suzerainty.

Waliszewska’s rendition, however, shifts the battlefield into a fantastic landscape, seasoned with fantasy tropes. Here the conflict plays out between forces of beauty and evil—the latter marked with swastikas. Yet the “fascists” are scantily clothed rather than armed, and it must be noted that warrior women and their adversaries share an unsettling level of stylized coolness. Hybrids, mermaids, and patriotic dogs painted red and white seem to triumph over dragons and pigs that recall Orwell’s Animal Farm.

Is the artist irreverent, treating a serious subject too lightly? Is the conflation of epochs with Witcher‑like visuals even permitted? Yet we recall recent faux‑pas in the manosphere, including the October 2025 revelation of young Republicans’ text messages making light of gas chambers and slavery, excused by J.D. Vance as “just kids.” Against such trivialization, Waliszewska’s mermaids and patriotic dogs insist on clarity: fascists must be recognized for what they are, even when they try to cloak themselves in the language of “cool” or slip into admiration for dictators who “did some good things.” Gothic allegiance here becomes surveillance, not of us, but by us: we observe, we measure, we test the bonds, we refuse the erasures.

Loyalty flickers like a candle; fealty binds like a chain. Together they reveal the gothic paradox: devotion as both sanctuary and prison. The gothic lesson is clear: authority that demands fealty will eventually betray. What remains is not passive endurance but active vigilance. We are the ones who watch, who test, who confront, who name betrayal when it appears. In that confrontation lies the possibility of transformation, where memory becomes resistance and reading itself becomes a form of guardianship.

Yet the lesson of this issue is not only that we are haunted by these bonds, but that we must also become their observers. Gothic allegiance is no longer a claustrophobic surveillance of the subject or pure escapism, but a deliberate practice of vigilance, of holding power to account. In this confrontation lies the possibility of transformation, where the body itself becomes archive and vessel, carrying memory into resistance. Luckily, reading never harmed anyone.